How fast can we learn? Part 1

learningPreface

In school I did not like to remember things. When I was told to learn the multiplication table, I thought - ‘what a waste of time!’. Well, I was wrong in this case and sometimes I find it very helpful. But It seems, it’s not that I did not like the multiplication table, it’s the process of memorizing that I did not like. And quite honest I still don’t. The process of repeating some information n times is dull and unappealing to me. Wouldn’t it be great if we could read information one time and memorize it at once?

In computer programming we have this notion of reusing code. We try to reuse our own code, but most of the time we reuse someone else’s work. This is so typical for programming, that we are not always aware of how much information we reuse. In web development we reuse tools, frameworks, preprocessors, interpreters, compilers. Each of these tools in turn reuses other tools, up to the point where code compiled to the binary language. Undoubtedly our work would have been much more complex if we did not have all those tools. Imagine writing a web program with processor instructions. These tools allow us to write a more concise program and focus only on the main goal of the app, abstracting low level interactions. Can we do the same level of reuse in our memory?

If we could, we probably could reuse some elements we built for previous tasks to come up with the result for a current task. I really like the analogy with the computer program here. Computer program takes an input, defines a set of commands on the input (algorithm) to receive a desired output. It seems, our brain works in the same way. We have an input, or resources (our body, knowledge, material), and output - goal we should achieve. The brain’s work is to provide a set of commands to get to the output. But what does it have to do with learning?

Learning highly depends on our memory. The more our memory capacity the more we can learn. The more efficiently we can optimize our memory the higher capacity it has. How can we do this? Can we reuse our memory blocks, in the similar way we reuse programming tools?

Memorizing process

As I mentioned earlier the process of repeating information does not seem right to me. Or to put in other words, it’s not seem right to my brain. The brain does not see a reason to repeat something n times. When our brain does not see a reason he does not have motivation to do it. We can make different tricks trying to deceive it, by promising our brain a ton of money, for example, if he learns this. Or repeating information before sleep, because someone taught us we keep memorize better this way. Or making exercises, since exercises increase the realease of chemicals in our brain that could improve memorization. But the reality is - without motivation, or without seeing results, our brain won’t be eager to do anything. And even if we manage to remember something this way, it will quickly fade away if we won’t use this information. How can we remember information better, ideally reusing other blocks that are already stored in memory?

If we imagine the process of memorization as a computer program, then this program would take data and define a set of instructions to store it: data -> instructions -> memory. So it seems to save information we need a set of instructions or algorithm. How would this algorithm look like?

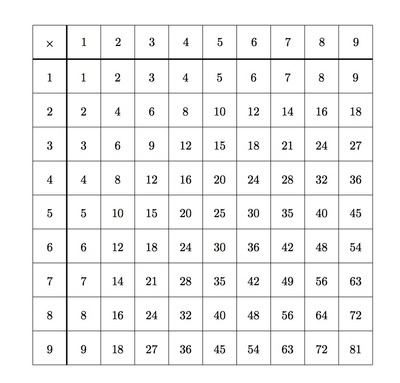

Let’s look at the multiplication table example. If we look at the row that multiples everything by 1, we can quickly see a pattern that every number multiplied by one is equal to that number or n * 1 = n. Also called identity. It seems it’s not necessary for us to remember anything here, because we know what identity is, and we quickly can use this information to get results from n. If we look at second row, row that multiples every number by 2, we can see a pattern too: n * 2 = n + n. So we can quickly return 2 * 4, by adding 2 fours and getting 8. Knowing that 2 is also a double, we probably don’t need to remember anything here too. Now let’s look at 8th row. Let’s say we need to find out result 8 * 7. We know that it is equal to 8 + 8 + 8 + 8 + 8 + 8 + 8. That is rather hard to calculate. But we know that 8 is also 2 * 4, so 8 * 7 = 2 * 4 * 7 = (7 + 7) * 2 * 2 = (14 + 14) * 2 = 28 + 28 = 56. It seems we can rather easy return result of every n * n, * where n < 10, given we know addition and multiplication logic. Or on other terms - reusing addition results and applying a multiplication algorithm. If that is the case, then we don’t need to learn anything new.

You can say - “But that takes time! If I know that 7 * 8 equal to 56 I will give result right away!”. That’s fair. But when you memorize something you use capacity of your memory. When you write something to it, you decrease it’s capacity. Next time don’t be surprized you don’t remember some of childhood memories. On the other hand, if we have a set of rules, we may not need to remember anything at all. Or if we do, that probably will be some algorithm. If we construct it correctly this algorithm will reuse memory that we already have (meaning saving capacity) and might be also reused later in other tasks (division for example). But there is more to it!

If we use some value often, say calculating 2 * 2, it’s result will organically be saved in memory, even without our attention! And this way we wouldn’t have to go through the process of memorizing things artificially. We just have to define the rules we use to get to the result. If we use some operation frequently, result of this operation will be saved in the memory register (daily memory). If brain sees that that this result is used more frequently (from day to day) than he can store it in long term memory. The best thing is that we don’t have to worry about it at all! Our brain will do all the work for us. And If so happens we’ve never used multiplication table, then we left with memory free of information we don’t need and with much better mood!

This process is called interference. There is retroactive interference, when learning new information makes it harder to recall old information and proactive interference, where prior learning disrupts recall of new information. Although interference can lead to forgetting, it is important to keep in mind that there are situations when old information can facilitate learning of new information. Knowing Latin, for instance, can help an individual learn a related language such as French – this phenomenon is known as positive transfer.

Feb 2020